This week the Ramsey County Law Library joins with libraries all across the nation in celebrating National Library Week. A brainchild of the American Library Association (ALA), the purpose of this event is to celebrate the contributions of our nation’s libraries and librarians and to promote library use and support. After all, as the ALA’s Freedom to Read Statement begins, “[t]he freedom to read is essential to our democracy.” Our library is also committed to the principles set forth in the ALA’s Library Bill of Rights.

This week the Ramsey County Law Library joins with libraries all across the nation in celebrating National Library Week. A brainchild of the American Library Association (ALA), the purpose of this event is to celebrate the contributions of our nation’s libraries and librarians and to promote library use and support. After all, as the ALA’s Freedom to Read Statement begins, “[t]he freedom to read is essential to our democracy.” Our library is also committed to the principles set forth in the ALA’s Library Bill of Rights.

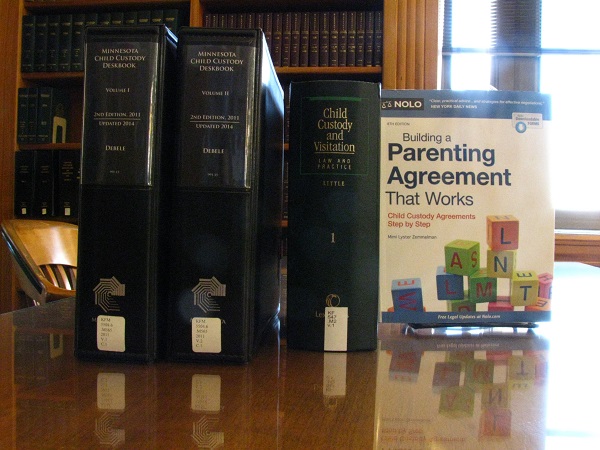

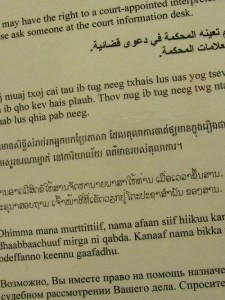

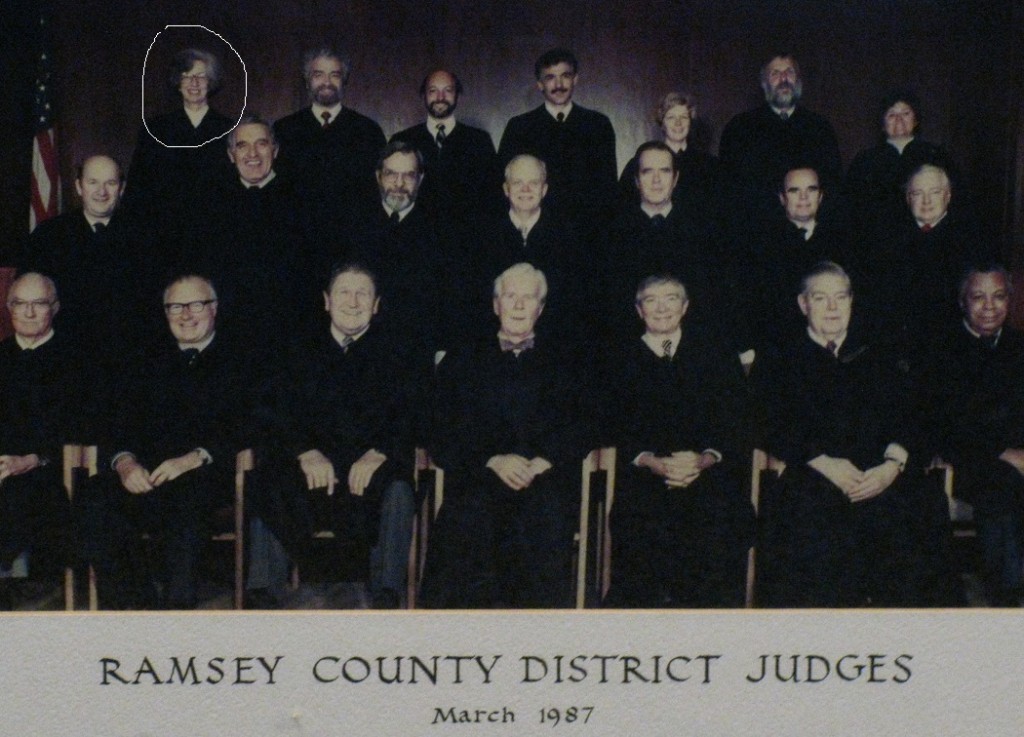

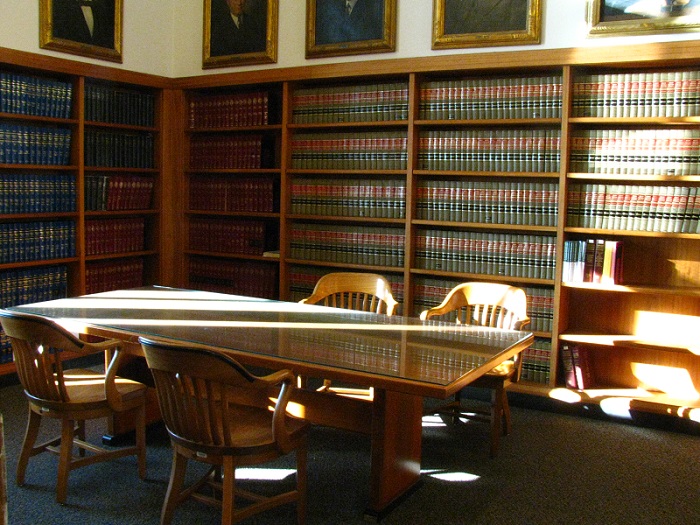

Our particular library serves the Second Judicial District Court, city and county officials, members of the local bar, and inhabitants of Ramsey County. It is covered under Minnesota Statute §134A, which governs the establishment and operations of county law libraries in Minnesota. In particular, §134A.02 requires that “the use of the library shall be free to the judges of the state, state officials, judges of the district, municipal, county, and conciliation courts of the county, city and county officials, members of the bar, and inhabitants of the county.” (This contrasts to county law libraries in some other states, where access might be by paid subscription or only for local attorneys.) So when people ask if our library is open to the public, the answer is an unequivocal “yes.”

Best-selling author David Baldacci is serving as Honorary Chair of National Library Week. Visitors to the library this week can register to win one of three Balducci political thriller novels, plus pick up a free pocket Constitution or a word game.