As President Trump interviews his short list of U. S. Supreme Court candidates, various media outlets inundate us with the political overtones and sneak previews of who might be nominated. The notoriety and long-term significance of a Supreme Court Justice are historic in American government. Even George Washington, in his 1789 letter to John Jay (the first Chief Justice) stated “It is with singular pleasure that I address you as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, for which your commission is enclosed….and I have a full confidence that the love which you bear to our country, and a desire to promote the general happiness, will not suffer you to hesitate a moment to bring into action the talents, knowledge and integrity which are so necessary to be exercised at the head of that department which must be considered as the keystone of our political fabric.”

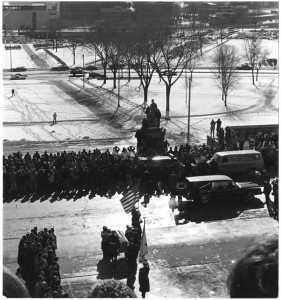

Minnesota has the distinction of having sent three notable men to the U.S. Supreme Court. They are Pierce Butler (1923-1939), Warren Burger (1969-1986) and Harry Blackmun (1970-1994). These three Justices also had ties to St. Paul and Ramsey County, according to For the Record: 150 Years of Law & Lawyers in Minnesota (Minnesota State Bar Association, 1999):

Pierce Butler—although he was born in Dakota County, he moved in 1887 to St. Paul and joined a law firm before being elected Ramsey County attorney in 1893 and 1895. He maintained a private practice in the law firm Butler, Mitchell, & Doherty. President Warren Harding nominated Butler to the Supreme Court in 1923.

Warren Burger—born in St. Paul, Burger attended the St. Paul College of Law and was admitted to the bar in 1931. He joined the St. Paul law firm of Boyesen, Otis, Brill & Faricy. He was later appointed to the U.S. Court of Appeals. In 1969 Richard Nixon nominated Burger to replace Chief Justice Earl Warren.

Harry Blackmun—Blackmun graduated from St. Paul’s Mechanic Arts High School and then attended Harvard. In 1932 his first job out of law school was with Judge John Sanborn at the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals; Sanborn had been a Ramsey County judge in the early 1920s. Blackmun also served as an adjunct professor at the St. Paul College of Law. President Richard Nixon nominated Blackmun to the Supreme Court in 1970.