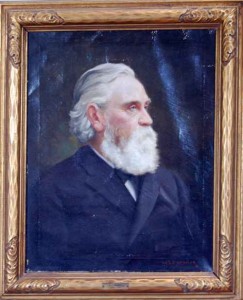

Charles Eugene Otis was born May 11, 1846 near Kalamazoo Michigan. He received his BA from the University of Michigan in 1869. He taught school for a time, and was Superintendent of Schools in La Porte, IN from 1869-1871. Charles Otis married Elzabeth Noyes Ransom of Kalamazoo in 1874.

He came to St. Paul in 1871 to work in the law firm of his brother George Otis. He was admitted to the MN bar in 1875. When George died in 1883, Charles formed a new partnership with his brother Arthur. He was appointed to the Ramsey County District Court in 1889 following the death of Judge Levi Vilas. He served two terms, leaving the bench in 1903. He thereafter resumed private practice with his son, James C. Otis.

Judge Otis served on the St. Public Library Board from 1896-1899. He also served on the St. Paul City Council, where he was instrumental in bringing the Minnesota State Fair to St. Paul. It should also be noted that he was the great uncle to a prominent American historical figure. His brother, Alfred G. Otis, was a U.S. District Court Judge in Kansas. Alfred raised his granddaughter in Atchison Kansas, who grew to be the aviator, Amelia Earhart. Judge Otis died on November 8, 1917. He left behind son James C. Otis and daughter Maribel R. Otis. No obituary is available for him and his burial place is unknown.

The Law Library has on display judicial portraits of past Second Judicial District Court judges, going back to 1857. If you have any information or commentary about Judge Otis, please leave a response or send us an e-mail. To view the portraits in person, visit us on the 18th floor of the Ramsey County Courthouse.

![file000205605496[1]](https://ramseylawlibrary.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/file00020560549613-300x199.jpg)

![file000288943151[1]](https://ramseylawlibrary.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/file00028894315113-150x150.jpg)

![file0001711682994[1]](https://ramseylawlibrary.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/file000171168299411-300x224.jpg)

![file0001568639492[1]](https://ramseylawlibrary.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/file00015686394921-300x225.jpg)

![9781595588692_p0_v2_s260x420[1]](https://ramseylawlibrary.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/9781595588692_p0_v2_s260x4201-202x300.jpg)

![file5721298196911[1]](https://ramseylawlibrary.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/file572129819691111-300x200.jpg)