The beginnings of Minnesota’s judicial system could hardly be more humble. In fact, its central player was anything but a respected legal figure.

The beginnings of Minnesota’s judicial system could hardly be more humble. In fact, its central player was anything but a respected legal figure.

Minnesota was established as a territory in 1849. Prior to that time there were local justices of the peace in the area, who likely thought they handled local justice needs just fine, thank you. But the day Minnesota’s territory status became official, President Zachary Taylor appointed David Cooper and Bradley Meeker as justices to the territorial supreme court, and Aaron Goodrich as its chief justice. Goodrich’s selection was probably a return favor for the campaigning Goodrich had done to get Taylor elected. Goodrich was a native of New York who later moved to Tennessee. He likely would never have studied law, but the failure of his family’s bank in 1838 probably motivated him to complete his legal studies while in Tennessee. He was one of the last members of the Whig Party, and was serving in the Tennessee Legislature when he was appointed to Minnesota’s territorial supreme court.

This ad hoc bench of three justices was predictably informal. Minnesota territory had been split into three judicial districts, and each of the three justices served as the district judge for one of the districts. Then, the three together would make up the higher court. Goodrich presided over Minnesota’s first, or Stillwater district, with St. Paul’s Mazurka Hall serving as the “courthouse.” This building left much to be desired, as litigants once needed umbrellas due to failure of the leaky roof to keep out a rainstorm. Apparently Goodrich was also known to nurse a glass of liquor and a wad of tobacco as he presided over his court. Meanwhile, American House in Saint Paul would serve as the first “judicial center” for the territorial supreme court, but the second and third terms were moved to the local Methodist Episcopal Church. (This interesting article about Goodrich reported that the local gossip was that Goodrich’s relationship with the landlady of American house was more than just business.)

Goodrich himself accomplished little to establish himself as a popular legal figure. To start, he had been tasked by a commission to prepare a system of codified law for Minnesota, but he was not a fan of either law’s codification or its strict application. (Read his dissent in Dosnoyer v. Hereux 1 Minn. 17 (1950) to understand his frame of mind.) The result was a loose collection of provisions, one stating that questions not otherwise answered in his written compilation should be resolved by the “ancient statutes.” There was also a general dissatisfaction with him among locals, and subsequent lobbying to have him removed. Even territorial Governor Alexander Ramsey believed that Goodrich possessed “utter incapacity for his place.” President Fillmore assumed the presidency in upon the death of Taylor in 1850, and removed Goodrich for what he referred to as his “incompetency and unfitness.” Goodrich practiced law after his removal, but his most notable client, Souix Indian “Zu-ai-za,” would be convicted of murder and hanged in Minnesota’s first official execution. He made few friends when he later wrote a book attacking the character and motives of popular historical explorer Christopher Columbus. Goodrich was also a charter member of the Minnesota Historical Society, however, and one of the founders of Minnesota’s Republican party.

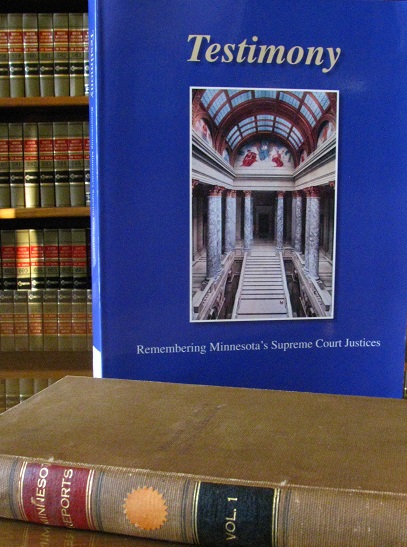

The fact that we expect a certain competence and decorum from our judicial officers may be more than just a craving for fancy formality. It may have been partly the result of the relatively poor impression made by Minnesota’s first chief justice. To learn more of this piece of Minnesota history, consider checking out Testimony: Remembering Minnesota’s Supreme Court Justices, written and published by the Minnesota Supreme Court Historical Society. Meanwhile you can read this excellent William Mitchel Law Review article.