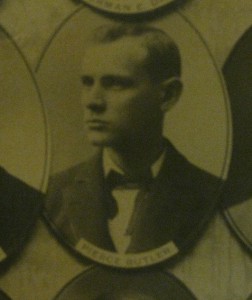

This week marks the anniversary of the passing of one of Minnesota’s most overlooked historical legal figures. He was none other than the first U.S. Supreme Court Justice from Minnesota, who spent his early professional years prominently in the Saint Paul legal community.

Pierce Butler was born in a log cabin in Waterford, Minnesota (about 35 miles south of Saint Paul) to Irish Potato Famine immigrant parents. He was the sixth of nine children. Schooled in Latin and German by his father, young Pierce began teaching at the county school when he was fifteen. He attended high school at Carleton College, and then enrolled in the regular academic program at Carleton after being rejected for admission by West Point. Upon graduation Butler took a legal apprenticeship with the firm of Pinch & Twohy of St. Paul, in lieu of enrolling in law school. (He was one of the last lawyers to be trained in the old tradition of “reading law.”) He was admitted to the bar in 1888. He married Annie M. Cronin (sister-in-law of his boss) in 1891. He and Annie eventually had eight children.

Butler served as assistant Ramsey County Attorney under Thomas O’Brien, and was elected Ramsey County Attorney himself in 1892. After serving two terms, he returned to private practice in Saint Paul in 1896. He was fond of debates with his friend (and later Judge) Frederick Dickson. Butler was an ardent backer of economic property rights and opponent of government intervention. He had an adversarial courtroom style that earned him the name “Fierce Butler,” for he was known to grind witnesses on the stand to bits. In 1908, Butler was elected President of the Minnesota State Bar Association. He represented numerous railroads before the U.S. Supreme Court (including those held by James J. Hill). He also became close friends with William Howard Taft as the latter was appointed to the Supreme Court. Through Taft’s influence, Butler himself was nominated for the United States Supreme Court by President Warren Harding in 1922. Butler had served on the Board of Regents at the University of Minnesota, and his opposition to “radical” and “disloyal” professors made him a controversial Supreme Court nominee, with both progressive groups and the Ku Klux Klan opposing his nomination. (He was Catholic.) Butler was nonetheless confirmed by the Senate on January 2, 1923.

As a Supreme Court Justice, Butler continued to be an ardent supporter of property rights, and a fierce opponent of government search and seizure where criminal defendants were concerned. (See his dissent from the opinion expressed in Olmstead v. United States which upheld federal wiretapping of telephone lines.) Butler was nicknamed one of the conservative “Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse” for his unwavering opposition of FDR’s New Deal policies. Predictably he became a prolific dissenter as the Court grew more liberal, dissenting in 73 cases from 1937 to 1939. He died on November 16, 1939 at the age of seventy three.

Forgive yourself if you were unaware of Butler’s legacy, which is rather elusive. His opinions tended to be on technical areas of law such as utilities regulation and taxation, which don’t generate the same level of public interest as other areas of law. He had many friends, but was a private person who eschewed public engagement. (Upon his deathbed, he ordered his clerk to destroy anything Court related, other than published opinions.) Much of this information here can be found in an excellent look at Butler’s life written by David R. Stras and published in the Vanderbilt Law Review in 2009. (This article can be a delicious history read for your Thanksgiving break!)